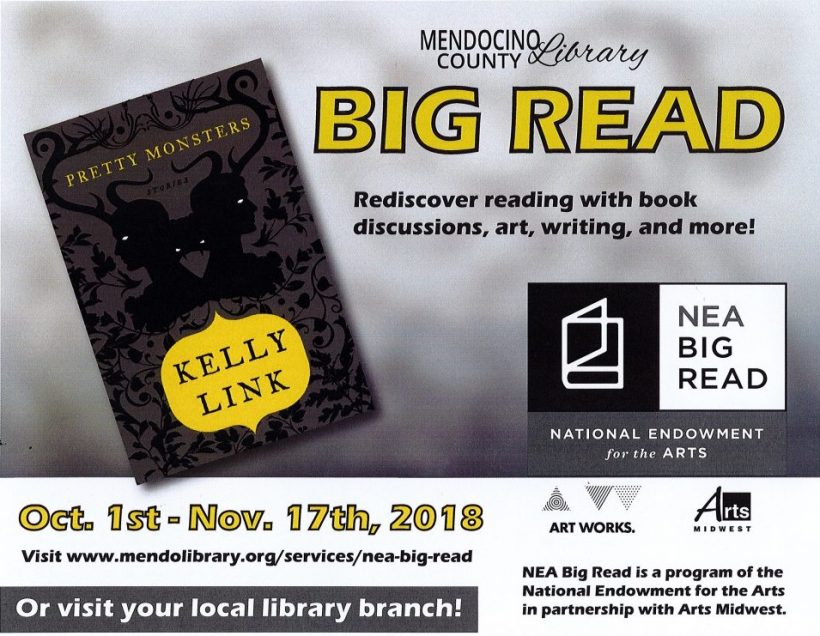

NEA BIG READ 2018

Adult Book Club discussion

Thursday, October 25, 2018, 7-8 pm

(following the Tales of Transformation performance by Darryl “Oasis” Hasten)

Get your FREE copy at any Mendocino County Library Branch starting October 2nd then join in the discussion.

PRETTY MONSTERS by Kelly Link

Overview

Neil Gaiman says Kelly Link, a National Endowment for the Arts creative writing fellow, should be declared a “national treasure.” Holly Black, author of The Spiderwick Chronicles, calls Link “a flat-out genius.” “In a place few writers go,” writes TIME, “a netherworld between literature and fantasy, Alice Munro and J. K. Rowling, Link finds truths that most authors wouldn’t dare touch.” Salon describes her as “an alchemical mixture of Borges, Raymond Chandler, and Buffy the Vampire Slayer.” Selected as Amazon’s Best Teen Book of 2008, Pretty Monsters is Link’s critically acclaimed anthology for both adult and YA audiences. Writes Booklist (starred review): “Her conception of fantasy is so unique that when she uses words like ghost or magic, they mean something very different than they do anywhere else. Perhaps most surprisingly … is Link’s dedicated deadpan delivery that drives home how funny she can be.” These stories, writes School Library Journal, make “the weird wonderful and the grotesque absolutely gorgeous.”

Introduction to the Book

“Her stories are about more than strangeness, more than the fantastic—they’re about inclusion, diversity, and acceptance of alternate world views.” — Lit Hub

Though all but one of the ten magical and macabre stories in Kelly Link’s collection Pretty Monsters were written for young adults, several of them first appeared in publications for adults, garnering Link a cross-generational fan base. The heroes of the stories are mostly teenagers in familiar settings grappling with angst and alienation, awkwardness and awakening desires. That they are also grappling with unexpected monsters, ghosts, wizards, gods, aliens, dueling librarians, pirate-magicians, shapeshifters, possibly carnivorous sofas, and undead babysitters should give readers a hint to keep their expectations in check. Pretty Monsters is part-haunted house, part-fun house, part-safe house, and part-something that doesn’t resemble a house at all.

“I like writing from the point of view of children, or young adults,” Link told One Story. “They’re in this weird transitional space, between worlds. Their actions have real consequences, but that doesn’t mean that they’re taken seriously…. They want things with a kind of great and terrible intensity that makes them great characters to write about…. When I write about adults, I’m most interested in writing about adults who have retained some of these qualities….”

The Hugo award-winning story “The Faery Handbag” draws inspiration from myths and folklore. A girl is tasked by her grandmother to be the guardian of a black, hairy, 200-year-old family heirloom purse that’s home to a whole village. Open it one way and it’s just a purse; open it another and it’s either the village itself—which, if you go into the bag to see it, you might not return for 100 years—or the dark, threatening land that smells like blood where the guardian dog of the purse lives. The girl makes the mistake of sharing the story of the bag with her boyfriend who gets too curious. Said Link: “I’ve always loved stories where the insides of something were bigger than the outside” (One Story)….

Link’s dry humor and witty dialogue are on full display in stories like “The Wrong Grave” about a boy who digs up the grave of his girlfriend to retrieve a poem he wrote and mistakenly buried in her coffin. ….

Kelly Link (b. 1969)

Kelly Link (b. 1969)

“Link is so beloved by her fans that she makes that ubiquitous epithet, ‘cult-favorite,’ seem eerie in its potential for literal truth.” — Jezebel

Kelly Link was born in Miami, Florida, where she lived in a “half-finished development” for seven years, a place where her father, a Presbyterian minister, chased peacocks off the roof of his car in the morning. There was a coral reef nearby covered in a thin layer of topsoil where a fire once broke out, she told Publishers Weekly. “Our lawn smoked for days. It was a pretty fantastical landscape.” The rest of her childhood was spent moving around: from Chattanooga, Tennessee; to Glenside, Pennsylvania; to Greensboro, North Carolina. As a teenager, she went on a lot of car trips, owned a pet boa constrictor named Baby, and “spent a lot of time in malls trying to decide if I wanted to buy a candle shaped like a dragon or a candle shaped like a schnauzer” (Publishers Weekly).

She loved to be scared, and she loved to read. She had “lots of interesting babysitters” who told “really good ghost stories” (Strange Horizons), and parents who loved books. They “could be talked into reading just one more chapter of C. S. Lewis’s Narnia books, one more chapter of The Hobbit. I followed them around the house, book in hand” (The New York Times). Later, when she could head to the library herself, she read books by Ursula K. Le Guin and other writers who wrote for both children and adults. “I became deeply attached to an edition of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz that belonged to the dentist’s office. It wasn’t in great shape, by which I mean someone had bled on it. Maybe multiple someones. She wasn’t happy about it, but my mother finally bought it for me so we could bring it home” (The New York Times).

Shortly after graduating from Columbia University in New York, Link won a sweepstakes while living in Scotland and got free travel around the world; she made it to New Zealand, Malaysia, Thailand, Fiji, Indonesia, and the Cook Islands. “You had to answer three basic geographic questions, and then the tie-breaking question was, why do you want to go around the world? I wrote down, ‘Because you can’t go through it,’ and that was how I won” (Publishers Weekly).

Link met her husband, Gavin Grant, working at a used bookstore in Boston; their wedding was 11 days after 9/11. “I might have been a clerk by profession, but in my heart I was a 40-hours-a-week browser” (The New York Times). In 2000, they founded Small Beer Press, a leading publisher of literary fantasy and science fiction, including Link’s first two, critically acclaimed collections of stories: Stranger Than Fiction (2001) and Magic for Beginners (2005). Link shopped around her books to major publishing houses, but short story collections, they told her, were poor financial risks. So she decided to self-publish, in part to keep control of the process and the product, and it paid off. “Every part of the publishing experience was miles better than I could have anticipated, but we worked very hard, too, to make sure that we didn’t muck it up” (Valley Advocate). One decision they made was to include illustrations by Shelley Jackson, the artist/writer known for the “Skin Project,” a novella published exclusively in the form of tattoos on the skin of volunteers, one word at a time. (Check out Link’s author photo.)

Link’s many writing accolades include three Hugo Awards, a Nebula Award, a Locus Award, a World Fantasy Award, and an NEA fellowship in creative writing. Recently, she was named a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize for her collection Get in Trouble, which she published with Random House in 2015. “I need a lot of distraction to work,” Link told Electric Lit. “I have my headphones on, I’m checking email, I look at Twitter and Tumblr, and drink a lot of coffee….”

Questions to think about as you read Pretty Monsters (abridged or amended from NEA website): You are welcome to print these questions, complete them and return them to the library (or email them to hessd@mendocinocounty.org) prior to the Oct. 25th discussion.

https://www.arts.gov/national-initiatives/nea-big-read/pretty-monsters

- As the narrator tells us in “The Wrong Grave,” the poet Dante Gabriel Rossetti buried some of his unpublished poetry with his dead wife, Elizabeth Siddal. Later, he dug up her grave so that he could get the poems (his only copies) back. Is there anything that you can imagine digging up a grave to retrieve? How does this story make you feel about poetry or poets?! Do you like the humor in the story?

- The characters in “The Faery Handbag” like to frequent thrift stores. They have a theory that “things had life cycles, the way that people do.” Do you ever wonder what stories surround your previously-owned possessions? The faery handbag, in fact, is a family heirloom over 200 years old. Do you have any mysterious family heirlooms? Does your family tell stories of your ancestors that don’t quite seem to add up?

- There is an alien invasion at the end of “The Surfer.” There’s also a pandemic. In post-apocalyptic stories, these are two of the most common ways in which the world ends. But does the end of the story feel like an apocalypse? Dorn’s father loves science fiction. He hopes that the aliens are there to save mankind. Does the ending feel hopeful to you? It’s a challenge to write interesting (or funny!) apocalyptic literature. Was Kelly Link successful?

- If you have read any “Fractured Fairy Tales” or feminist re-tellings of famous fairy tales, how do they compare with Link’s stories, “The Cinderella Game?” Is this story itself a fairytale?

- Does Kelly Link show any special instincts as writer for teens’ relationships with their parents or the adults in their lives? Can you imagine the characters in these stories as adults? Would they be very different? Do you think that people stay the same as they grow up, or do they become almost entirely different people?

- Link has been commended by critics for, among other things, her humor. Did you find some of these stories—or parts of the stories—funny? Why? How would you describe her particular type of humor?

- Question from Librarian, Dan Hess. The final story in the collection feels homophobic to me. (This is a personal objection to the dialogue in a story, not a blanket rejection of the book or a dismissal of the author! Others may not have homophobia on their radar.) I am concerned that readers may encounter this book for the first time in this Big Read program, some of them young people who will see a book that gives homophobic comments a pass. Some readers will be oblivious to this section and may use such talk on others they know. This is how prejudice is passed along.

The problem is in the characters and dialogue of the last story, “Pretty Monsters.” Clementine is 12 and trying to be attractive to an older guy named Cabell (p. 351):

[Clementine suggests that Cabell kiss her. Cabell replies.] Don’t think I don’t appreciate the offer, Clementine,” Cabell said, “but hell, no.” “Oh shit, ” Clementine said. “You’re gay?” [She is projecting a common stereotype that a lack of interest in girls implies a guy is gay.] “No!” Cabell said. “And stop taking off your clothes, okay? I’m not gay, I’m just not interested. Not to be an a**hole, but you’re not my type.” [He tells her she’s underage for him and that’s the reason he wouldn’t kiss her. Cabell leaves, then Clementine cuts her feet on glass on the beach, requiring stitches. The reader thinks the homophobic exchange was a one-off, but then Clementine keeps up the homophobic needling in a chat with Cabell on page 356.] DARLINGSEA: you saved my life 2X now. u didn’t take advantage. u know, even tho I was drunk and obnoxious and sed that u were gay. 😉 TRUEBALOO: clementine, its ok. really don’t mention it. ok? DARLINGSEA: your not, right? i mean your not gay r u? even if your not im sorry about the tux. did the blood come out? TRUEBALOO: not last time i checked TRUEBALOO: dont worry about the tuxAs I said, I don’t identify Kelly Link, the author, with Clementine, the drunk, precocious 12-year old. But this exchange upholds a stereotype that boys are one of two things: straight and interested in girls or gay and could care less. Cabell is forced to answer her three times on the subject. The last time he says “not last time I checked.” How do you check if you’re gay? It’s not anatomical. DARLINGSEA implies that it was a shaming thing to a man to be called gay. “even tho I was drunk and obnoxious and sed that u were gay.” The author doesn’t include a real gay character in any stories in this book, so the offhand remarks by her characters stand alone. Imagine if all the characters in a book are white and a character only mentions another race once as a “cut-down.” How would we view the author?

8. If you could ask the author one question about these stories, or about writing them, what would you ask her?

Fort Bragg Library Mendocino County, California

Fort Bragg Library Mendocino County, California